Background

Puerto Rico has been a U.S. territory since 1898, and island residents have been U.S. citizens since 1917. For the first time in history, on November 3rd, 2020, as part of the Puerto Rico general election, a clear majority voted “YES” to request the Island’s immediate admission into the Union as a state. See the official results here.

Why now?

This vote comes on the heels of two other plebiscites held in 2012 and 2017, where a majority of voters rejected the current territory status and more voters favored statehood than any other non-territorial status option. Statehood opponents have claimed that the results were questionable because of their boycott of the vote through blank ballots in 2012 and low voter participation rate in 2017. Although in a democracy only the votes of those who participate in an election and choose a valid option can ever really count, Congress has hesitated to act on those prior results. This has made clear that for Congress to take action on resolving Puerto Rico’s ultimate political status, they need to know definitively that a majority of voters support a non-territorial alternative. Since statehood is the non-territorial alternative with the most support, asking this simple statehood YES/NO question was essential to show that an unquestionable majority of Puerto Ricans support it.

How was this vote different from previous plebiscites?

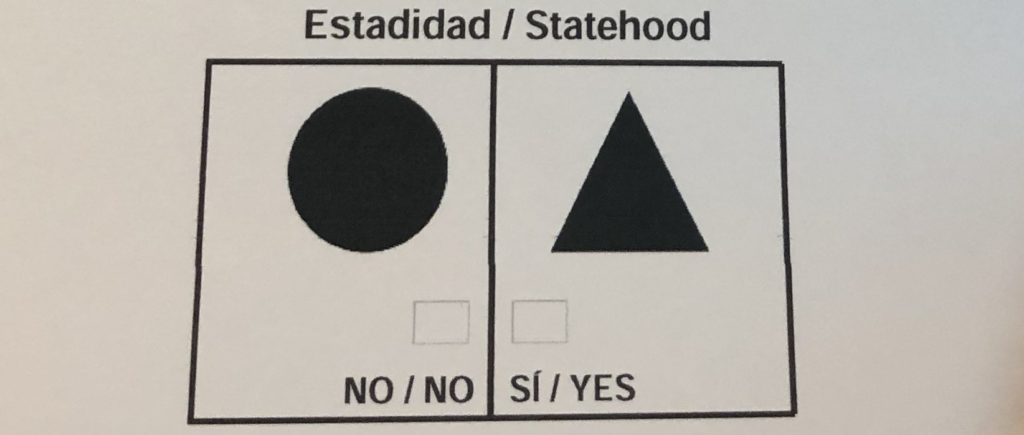

Although island residents have been asked multiple times in the past to vote on the island’s future political status options, the question of statehood has never been asked in such a simple, direct and immediate way:

Should Puerto Rico be immediately admitted into the Union as a state?

This straightforward format allowed everyone who opposed statehood, for any reason (i.e. they favor keeping the territory, want independence, etc.), to vote “NO,” and it allowed everyone who supported statehood (full voting rights and equality as U.S. citizens), to vote “YES”. The question asked if voters wanted statehood immediately to show Congress the urgency of taking action on the results.

Does this vote matter even though it was “non-binding”? Was there any precedent?

Yes. Alaska and Hawaii also confronted delays in getting Congress to respond to their calls for self-government and self-determination when they were territories seeking statehood. To address that, both of the territories voted in locally sponsored “non-binding” plebiscites expressing support for statehood. Those locally sponsored votes generated necessary pressure for Congress to pass their statehood admission bills, which required them to vote one final time before becoming a state. In both cases support for statehood grew significantly between the territory’s first locally sponsored “non-binding” statehood vote (58% in 1946 for Alaska & 67% in 1940 for Hawaii) and their federally “binding” final vote after Congress enacted admission legislation (83% in 1958 for Alaska and 94% in 1959 for Hawaii).

Does the plebiscite have support in Washington?

Yes. To ensure that Congress listens to this vote and acts on the will of the U.S. citizens of Puerto Rico, a bi-partisan group of House members led by Rep. Darren Soto (D-FL) and Rep. Jenniffer Gonzalez-Colón (R-PR) introduced H.Res.1113, a resolution calling for Congress to take action on the results of the plebiscite. The resolution had 23 cosponsors.

Many members have expressed support for the plebiscite and for Puerto Rico statehood including Sen. Marco Rubio, Rep. Rob Bishop, Rep. Donna Shalala, Rep. José Serrano and others. Rep. Raúl Grijalva (D-NM), Chairman of House Natural Resources Committee (with jurisdiction over territories), stated he’d be open to addressing the issue of statehood in committee. Similarly, Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) suggested that a discussion about statehood could also take place in the Senate. Both Rep. Stephanie Murphy (D-FL) and Rep. Jenniffer Gonzalez-Colón delivered statements on the House floor recognizing that the majority of voters chose to become a state and calling on Congress to take action.

Did low voter participation rates or boycotts undermine the validity of the results, like in 2017 or 2012?

No. This plebiscite was held concurrent with the general election, so the voter participation rate was 52%. This was vastly higher than in the 2017 plebiscite which obtained 23% participation, a rate that was normal for an election event scheduled outside a general election. No registered political party in Puerto Rico called for a boycott of this plebiscite. In fact, all political parties actively campaigned for either the “YES” (New Progressive Party) or the “NO” (Popular Democratic Party and Puerto Rico Independence Party) options, and a new party, Citizens Victory Movement, had some of its candidates campaigning for “YES” and others for “NO”.

Is it true that because US DOJ did not fund the plebiscite, it was not valid?

No. Congress has made clear in federal statute that Puerto Rico’s right to determine its future political status can be exercised with or without the use of a federal appropriation that requires U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) approval.

Exercising this right, Puerto Rico’s elected government, which was elected to seek statehood, enacted a law on May 16, 2020 providing for the “Yes” or “No” vote on statehood. Additionally, history shows us that when both Alaska and Hawaii voted in locally sponsored plebiscites that were not federally approved, and expressed support for statehood, those results helped pressure Congress to eventually pass their statehood admission bills.

Was the plebiscite ever challenged in court? And if so, what was the result?

Yes. In a decision by the Puerto Rico Supreme Court in the case of Vega Ramos v. PR State Elections Commission,the Court found that the statehood “YES” or “NO” plebiscite was a Constitutionally valid and non-discriminatory exercise of the right of self-determination of the U.S. citizens of Puerto Rico. In the Court’s words, “it permits all Puerto Ricans, on equal footing, to participate and express themselves in favor or against the ratification and implementation of the status option that was favored in the plebiscites celebrated in 2012 and 2017.”