Five counties in Oregon voted to leave their state and become part of Idaho. Will they be able to do that?

The Oregon vote

An organization called “Move Oregon’s Border for a Greater Idaho” hopes to move a group of Oregon counties into Idaho. The Oreganites say they are unhappy with their state’s liberal government, while Idaho looks forward to having some coastline.

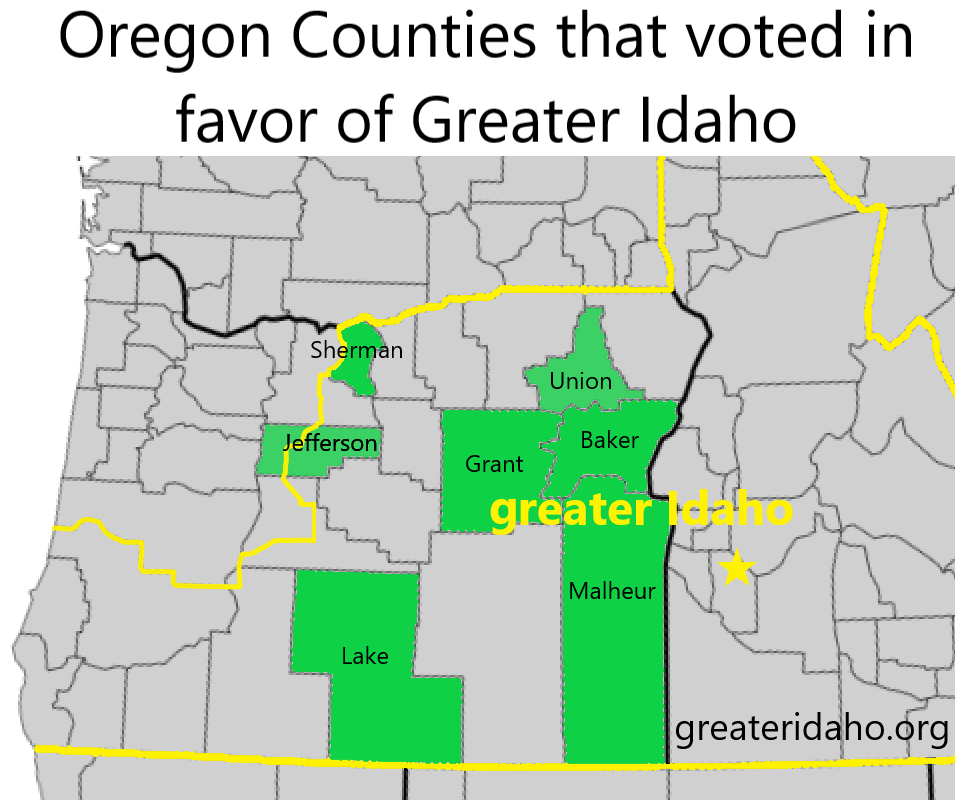

The five counties that held the vote saw, on average, a 62% majority for leaving Oregon. Turnout for the election ranged from 35% to 51%, with an average of 43%. Two other counties had already voted in favor of the proposal in 2020.

However, the votes weren’t actually declaring that the counties would move to Idaho. Grant county, for example, voted for “the Grant County Court to meet on the first Wednesday of every April, August, and December to discuss whether it is in the best interest of Grant County to promote the relocation of the Oregon-Idaho border.” That’s a vote to have a conversation, not a vote to move the border.

A spokesman for the tiny group spearheading the secession movement said, “If Oregon really believes in liberal values such as self-determination, the Legislature won’t hold our counties captive against our will. If we’re allowed to vote for which government officials we want, we should be allowed to vote for which government we want as well.”

The organization’s website says, “Idaho’s governor and the leadership of both houses of the Idaho legislature support the border relocation.”

The five counties, Sherman, Grant, Lake, Malheur, and Baker, do not form a single contiguous region. The two counties that voted for this in 2020, Union and Jefferson, don’t help. There are 8 more counties that would have to move to Idaho as well in order to keep all the counties connected in a single state.

Map courtesy of Greater Idaho

If the movement succeeds, Idaho would take over 75% of Oregon’s land.

Can Oregon and Idaho do this?

At first glance, this might remind you of Puerto Rico’s position. Voters said they want to become a state, and now they are waiting for Congress to approve. In fact, it is not the same situation at all, because Puerto Rico is a territory, not a state.

The Territorial Clause of the United States Constitution says this:

New states may be admitted by the Congress into this union; but no new states shall be formed or erected within the jurisdiction of any other state; nor any state be formed by the junction of two or more states, or parts of states, without the consent of the legislatures of the states concerned as well as of the Congress.

The Congress shall have power to dispose of and make all needful rules and regulations respecting the territory or other property belonging to the United States; and nothing in this Constitution shall be so construed as to prejudice any claims of the United States, or of any particular state.

The organizers of Greater Idaho point out that they are not actually proposing to make a new state. Neither Idaho nor Oregon is a territory any more, either. Both are now states, so they have rights and powers that a territory does not have.

The legislatures of the two states would have to agree, and probably to pass laws specifying their new borders.

State borders have changed in the past, mostly in the 18th century. South Carolina and North Carolina changed their border by a few miles in 2017, after more than two decades of negotiation. 54 homes were affected; some had been in North Carolina but ended up in South Carolina or vice versa. Some ended up being partly in one state and partly in another. The states are still working on sorting out the details for the affected individuals.

Must Congress get involved?

The U.S. Congress hasn’t gotten involved with the Carolinas. Idaho and Oregon think they will need approval from Congress. That is not clear from the U.S. Constitution.

The Hill lists three previous occasions when Congress has approved state border changes: Kentucky in 1792, Maine in 1820 and West Virginia in 1863. In fact, these were new states made by changing old states’ orders. They are therefore covered by the explanation in the Territorial Clause.

That’s not the case for Oregon and Idaho. A number of states have at some point proposed giving a few counties to another state, but none has ever succeeded.

Oregon’s state constitution foresaw the possibility. It has a section that says Congress would have to approve:

Such boundaries [can be] modified by appropriate interstate compact or compacts heretofore or hereafter approved by the Congress of the United States;

Idaho’s constitution doesn’t specify what to do in the case of a change of state boundaries. They could go along with Oregon’s rules. In that case, if the people choose to change their borders and the legislatures agree, the states would have to wait for Congress to approve their changes.

Oregon and Idaho both have representatives in Congress who could introduce a bill approving the change, work to get the bill through committee, and get the bill passed. Very few bills get passed in Congress, but it could happen.

The case of Greater Idaho is an interesting example of how states might choose to make changes…after they become states. As a territory, Puerto Rico is in a different position.

No responses yet