In 2005, Emilio Pantojas-Garcia wrote, “In 1952, Puerto Rico became a Commonwealth or Free Associated State.” He reminded readers that “Puerto Rico’s political system was that of a classic colony” before 1952 and admits that “Because the Commonwealth formula is not part of U.S. federal doctrine, the prevailing judicial interpretation is that Puerto Rico continues to be an unincorporated territory that belongs to but it is not a part of the United States.”

“Doctrine” is an interesting word to use. We would say that Puerto Rico, like a number of states including Kentucky and Massachusetts, has the word “commonwealth” in its name, but this has no legal meaning in the United States.

“Under Law 600,” Pantojas-Garcia continues, “the U.S.Congress and President retain sovereignty over Puerto Rico and can unilaterally dictate policy relating to defense, international relations, foreign trade, and investment. Congress also reserves the right to revoke any insular law inconsistent with the Constitution of the United States…Furthermore, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico does not have voting representation in the U.S. Congress.”

Differences of opinion

Pantojas-Garcia offers a realistic overview of the socio-economic position of Puerto Rico, and recognizes that supporters of the different status options have different understandings of the issues. “Pro-statehood and pro-independence supporters argue that Commonwealth is a colonial status because of the lack of effective representation and unrestricted congressional and executive power over Puerto Rico. Commonwealth advocates argue that this formula represents a compact among equals, which can be renegotiated to remedy its salient flaws.”

Himself a commonwealth supporter, Pantojas-Garcia imagines that the relationship between the United States and Puerto Rico is, first, a compact between equals. In fact, the Territory Clause of the U.S. Constitution makers it clear that Congress has the legal right to make decisions for Puerto Rico. By definition, this is not a relationship between equals; Puerto Rico’s government does not have the legal right to make decisions for the United States.

Pantojas-Garcia admits this inequity. “Lack of congressional representation, the incapacity of voting for the President, the inability to sign treaties with other nations, and unequal access to federally-funded programs are some of the problems flowing from the Island’s current status,” he writes.

And yet he also imagines that the relationship can be “renegotiated.” Compacts of Free Association can be renegotiated, and must be negotiated to begin with. Puerto Rico does not have a Compact of Free Association with the United States. It is not a free associated state, but rather an unincorporated territory. He lists “the pillars of the Commonwealth’s economic policies: (1) common defense, (2) common currency, (3) common citizenship, (4) selective application of federal labor laws and regulations, (5) federal tax exemptions and special quotas, and (6) local tax exemptions.” He does not admit that all three branches of the federal government have stated clearly that the “enhanced commonwealth” which he imagines is not viable under the U.S. Constitution.

Have things changed?

Pantojas-Garcia is a Senior Researcher and Professor of Sociology at the University of Puerto Rico. He wrote these things in 2005, but we can find the same sort of claims today. Former “commonwealth” supporters have generally stopped saying that Puerto Rico already is a freely associated state with a Compact of Free Association; recent Supreme Court cases have completely destroyed that myth.

Instead, they are now saying that Puerto Rico should be a free associated state with a COFA. The promises they make — still using the claim that “political will” is all that is needed to bypass the U.S. Constitution — are roughly the same ones they made when they supported “enhanced commonwealth.”

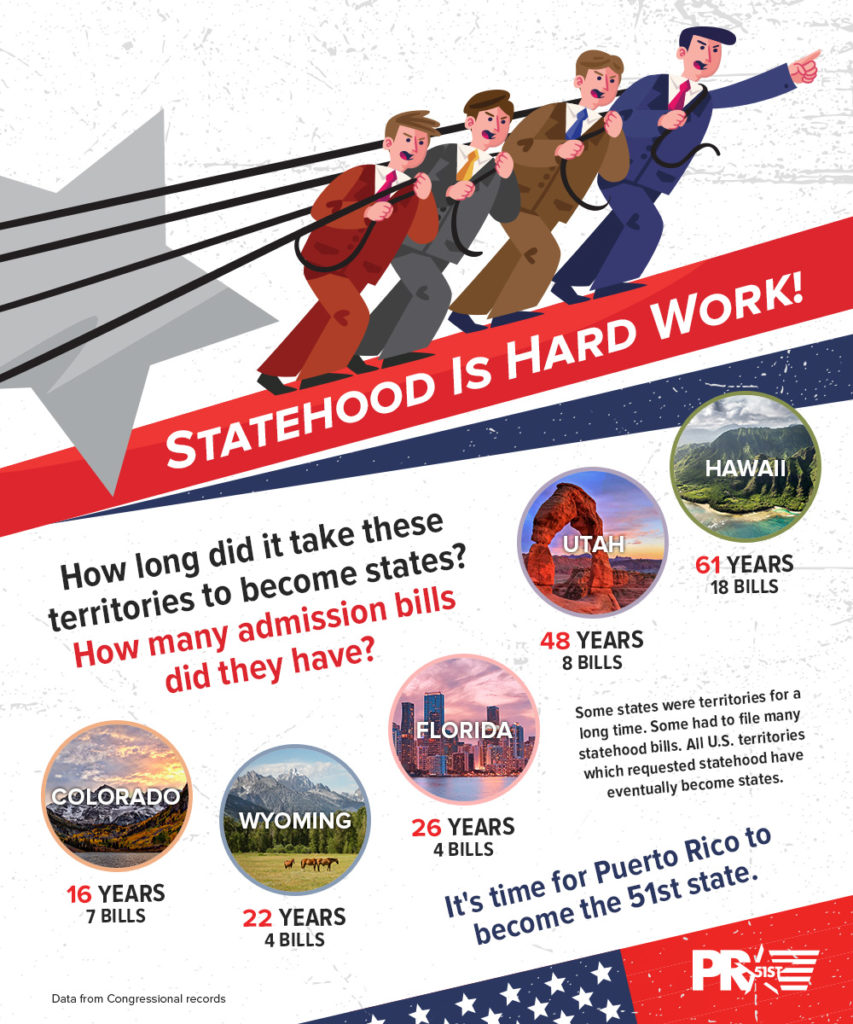

“Given the scant electoral support for independence and the difficulty of becoming the fifty-first state of the American union,” Pantojas-Garcia concludes, “the struggles for the expansion of citizenship rights, national identity, economic development, democratic representation, social justice, and security will most likely be advanced within the limits of the associated free state.”

The stories are the same. The facts also are the same: free association is not the same as enhanced commonwealth. Statehood guarantees expanded citizenship rights, democratic representation, social justice, and security. Every territory which has become a state has also seen economic development. Every state has its own cultural identity.

Is it difficult to become a state? We know that it is. Other territories have struggled for statehood and Puerto Rico will have to continue to struggle. But we are closer than ever before. This is the time to band together to work for statehood.

No responses yet