The Insular Cases continue to pop up in the headlines. These Supreme Court cases from the early 20th century set a precedent for the unincorporated territories of the United States, determining that they would not be protected by the U.S. Constitution. Increasingly, Members of Congress as well as civil rights organizations have called for these decisions to be repudiated and revoked. Recently, the Department of Justice made a clear statement against the Insular Cases. Observers — and members of Congress who have tried to legislate against these cases — think we may be on the verge of overturning these decisions.

Then what?

Would revoking the Insular Cases be like a Time Machine? Would the unincorporated territories automatically become incorporated? Would the U.S. Constitution immediately apply equally to Puerto Rico? Would U.S. citizens in territories be able to vote in presidential elections? Would federal benefits be equal for all citizens?

It’s easy to get the impression that this would be the case.

In fact, that would not happen. The Insular Cases did not change Puerto Rico and the rest of the territories from incorporated territories into unincorporated territories. They did not cause the Constitution, which had previously applied in the territories, to stop applying. Rather, the Supreme Court made it clear that Congress had not offered the insular (island) territories the same deal as the other territories. Most U.S. territories were inhabited mostly by U.S. citizens. But the new insular territories were not full of U.S. citizens. In some cases, Congress had already decided that they would not become states but would have independence when they were ready. In other cases, no decisions about the future had been made.

That was generally the point of the cases. With the island territories essentially in limbo waiting for Congress to decide, the Supreme Court determined that the new territories, while they waited for Congress to settle their status, were possessions of the United States, but not yet actually part of the United States. If the Insular Cases were to be revoked, then Congress would have responsibility for a clutch of territories inhabited by Americans — U.S. citizens and nationals — with no official political status at all.

Puerto Rico without the Insular Cases

Puerto Rico, with about three million U.S. citizens, is treated differently from states because it is a territory, not a state. It can continue to be a territory indefinitely because of the insular cases. If they were revoked, it could force the hand of Congress. The Supreme Court said that a territory, if it was an unincorporated territory, could remain a territory indefinitely. Without the concept of an unincorporated territory waiting around for Congress with no guarantee of eventual statehood, Congress might be forced to say whether Puerto Rico was on a path to statehood or not. If so, then the size of the population and the intimate connection of the economy and culture of Puerto Rico with the United States would make it obvious that Puerto Rico is ready for statehood. If not, then Puerto Rico could reasonably demand independence.

Even if Puerto Rico had to be treated equally with states and was fully protected by the Constitution, residents of the Island would not be able to vote for president or to have full representation in Congress without statehood.

Racist language

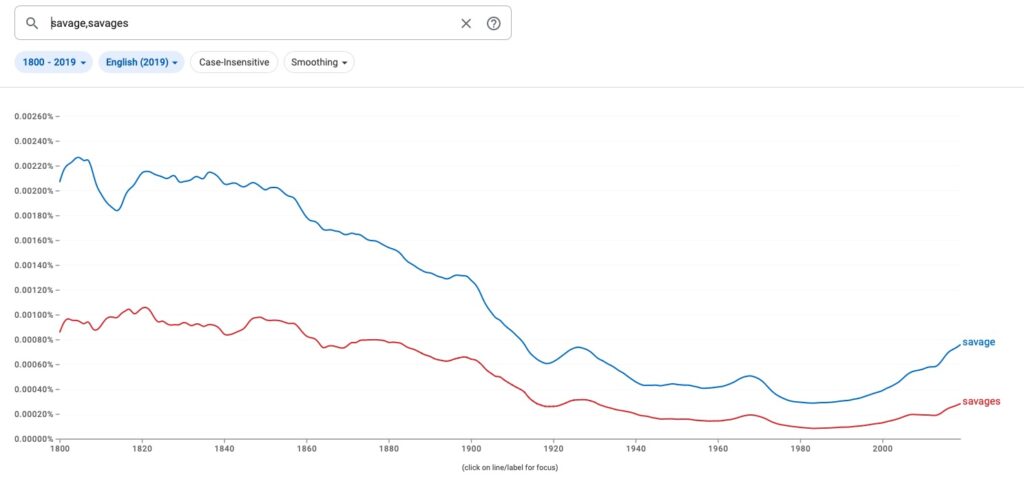

The Insular Cases decisions did contain racist language. They referred to the people of the insular territories, for example, as “savages.” The decisions were written between 1901 and 1922. The chart below shows how frequently the terms “savage” and “savages” were used in English writings over time. By the time of the Insular Cases, those expressions were already going out of favor, but they were used far more in the period from 1900 to 1920 than they were later on. We’re surprised to see that they are more common now than they were a few decades ago. Still, it’s a fair bet that many Supreme Court decisions from a century ago contained racist language. People used that kind of language freely in those days. That doesn’t make it acceptable, but it is not the central point of the legal problems around the Insular Cases.

The racist language used in the decisions in the Insular Cases reveals the racist attitudes that caused the Supreme Court of the time to accept the idea that people living on land in the possession of the United States might not be covered by the Constitution. But their decisions started off by saying that Congress hadn’t made the people citizens, so they weren’t covered. By the final case in 1922, they were saying that even though the people of Puerto Rico were by that time U.S. citizens, Congress still hadn’t made it clear that they were covered by the Constitution.

Is that a racist conclusion? Absolutely. But it still leaves the ball in the court of Congress. The Supreme Court said at the time that Congress hadn’t yet made their intentions clear.

Now, a century later, Congress still hasn’t made their intentions clear. It is Congress, not the courts, that needs to step up and fulfill their responsibility. The Puerto Rico Status Act is a way to accomplish that. By making clear to the voters of Puerto Rico what status options they are prepared to accept, Congress can move past the confusion of the Insular Cases. Puerto Rico can choose the preferred political status from the possibilities that Congress will act upon. Puerto Rico can finally have a permanent political status.

Tell your congressional reps that it is time to give up the ambiguity of unincorporated territory status at last.

No responses yet